Mutilation of Jérôme Rodrigues: the revelations of the policemen body cameras

In January 2019, during the Act XI of the Yellow vests protests, Jérôme Rodrigues’ eye was mutilated by the explosion of a de-encirclement grenade. INDEX obtained access to hundreds of hours of exclusive video footage and documents, which we analysed to produce a detailed reconstruction of the circumstances of the incident. Using videos recorded by the police bodycams, our investigation offers an unprecedented dive into the workings and dysfunctions of French-style crowd control.

| Date of incident | 26.01.2019 |

| Location | Paris (75), France |

| Consequence | Mutilation |

| Keywords | Maintien de l’ordre Grenade |

| Partner(s) | Le Média |

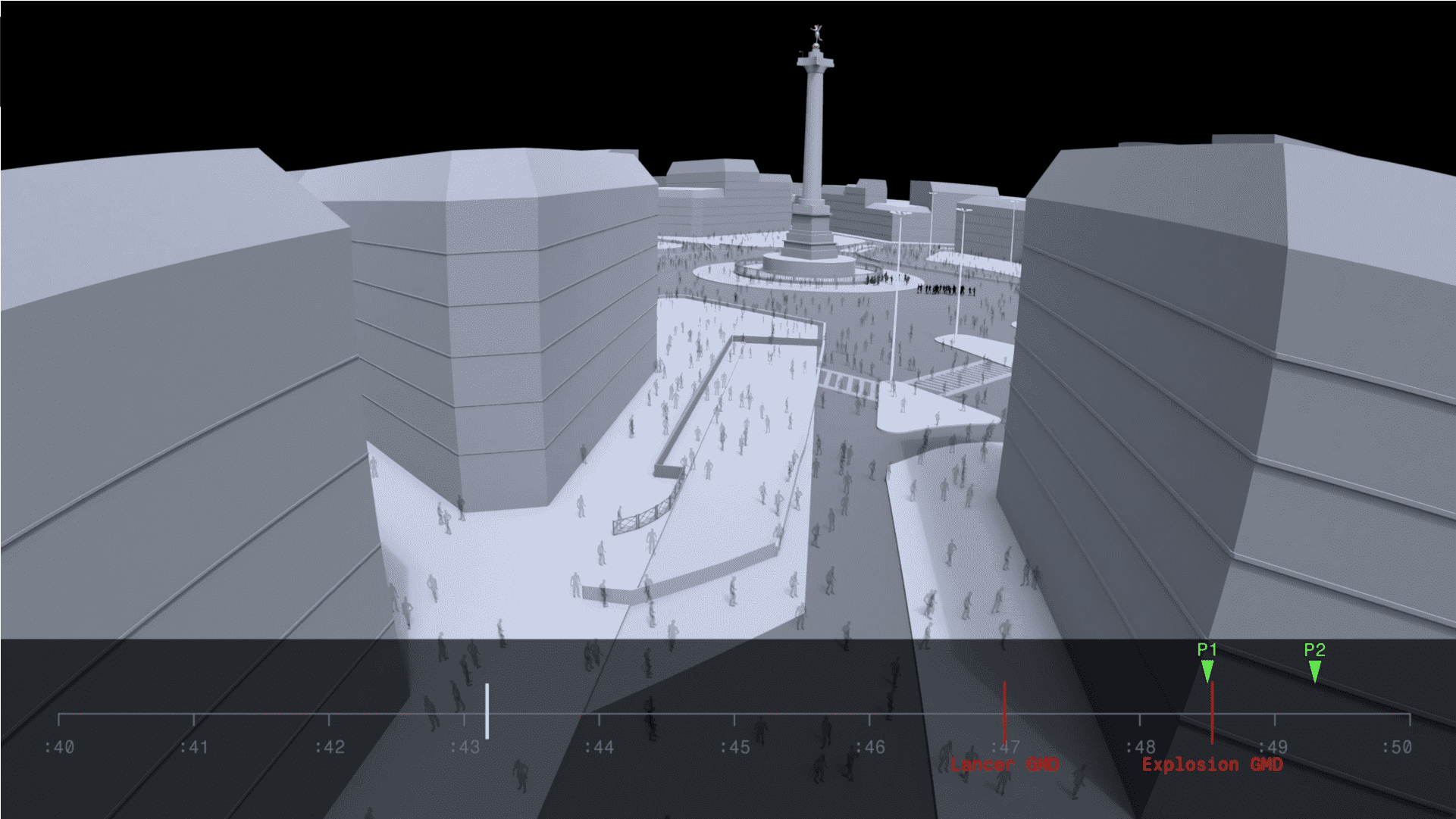

January 26, 2019, around 4:30 p.m. The situation is tense on the Place de la Bastille in Paris: the Act XI of the Yellow vests is underway, clashes have broken out between police and demonstrators. From his smartphone, Jérôme Rodrigues, 39, documents the demonstration by broadcasting a ‘live’ on his Facebook page, one of the movement’s most followed. He’s at the foot of the Colonne de Juillet, in the center of the square, when something suddenly exploses very close to him. The camera on his phone tilts then turns towards the sky, while continuing to stream its live feed: Jérôme Rodrigues is lying on the ground, hit in the eye by the pebble of a ‘grenade de désencerclement’, an anti-crowd de-encirclement grenade used by the French police. The injury will result in the permanent loss of his right eye.

Four years later, the case is still pending before the courts. However, the incident was filmed by dozens of cameras: those of the demonstrators and of the many journalists present on the scene, but also by urban video surveillance and by the body cameras worn by some of the police officers on the field that day. INDEX obtained access to all of these images and proceeded to cross-analyse them. After several months of investigation, we are now revealing a reconstruction of the incident which brings to light the precise circumstances of Jérôme Rodrigues’ mutilation.

A badly coordinated maneuver

On the afternoon of Saturday, January 26, 2019, the police are stationed around the entire perimeter of Place de la Bastille. They control the access and the exit of the demonstrators. In groups ranging from one dozen to several dozen officers, the police charge into the square, with the aim of arresting individuals. Certain groups of police officers are the target of projectiles thrown by demonstrators. The use of tear gas canisters is frequent. Surprised by the turn of events, many demonstrators showing no hostility towards the police are still present on the Place de la Bastille.

It is in this context that at 4:38 p.m., three police units – a squad from the Anti-Crime Brigade (BAC) and two from two different Security and Intervention Companies (CSI) – rush from the corner of the boulevard Bourdon towards the center of the square. The BAC agents had previously spotted a demonstrator who had allegedly thrown projectiles at the police and decided to arrest him. To cover their leap forward, they ask the CSI agents to follow them. In total, nearly fifty police officers are sent to the charge on the Place de la Bastille, with the apparent order to arrest a single individual.

«The different police units communicated very badly between them», subsequently declared Brice C., the police officer who threw the grenade which hit Jérôme Rodrigues, to the investigators of the IGPN, the French police institution charged with investigating its agents misbehaviour. «Everything didn’t go as planned», he explains: because of the heavy and cumbersome equipment they carry, the CSI police officers are unable to keep up with their colleagues from the BAC, in civilian clothes. «A mistake», summarizes in a hearing with the IGPN the brigadier-en-chef of the CSI Georges N., who recounts having stopped his agents in the middle of the square, just in front of the group of demonstrators amidst which was Jérôme Rodrigues.

A grenade thrown irregularly

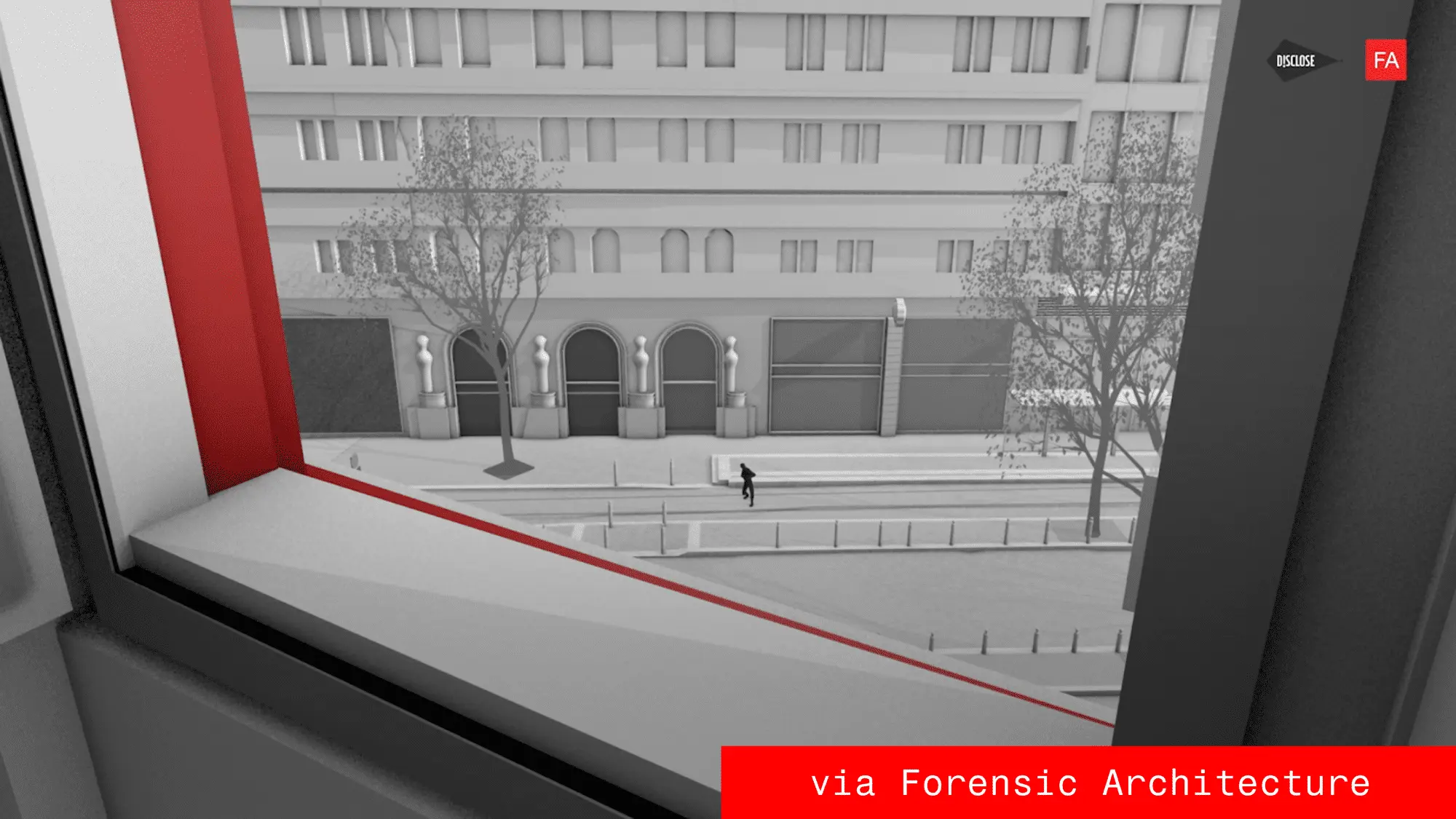

The footage of the policemen body cameras provide essential elements in order to understand the events. One of these cameras in particular, carried by the CSI agent located immediately to the left of Brice C., recorded the entire police maneuver. The analysis of this video shows that, during his run, officer Brice C. preventively draws a de-encirclement grenade from his pocket: when he stops in the middle of the Place de la Bastille, he is already holding the grenade in hand.

De-encirclement grenades are weapons officially classified as ‘war weapons’. They contain eighteen rubber projectiles which, when they explode, are thrown in all directions at an initial speed of between 400 and 500 kilometers per hour. Anyone within a radius of fifteen meters from the grenade’s explosion point can be violently impacted by one or more projectiles. The operating instructions of the de-encirclement grenade specify that it must imperatively be thrown «at ground level», because of its dangerousness when it explodes.

Image: INDEX Investigation.

The grenade throw performed by police officer Brice C. can be seen in three of the available videos. By triangulating the data from these videos, we were able to reconstruct the trajectory of the grenade in the 3D model. We found that the throw does not appear to be a regular one. The grenade is not thrown at ground level but takes a bell-shaped trajectory: it rises to more than a meter in height, bounces on the pavement, then explodes on the ground.

In his report drawn up the very evening of the events, police captain Lionel P., Brice C.’s hierarchical superior, indicates that his subordinate «had no other means of extricating himself than to use a de-encirclement grenade, by throwing it on the ground in accordance with the instructions for use». Such a statement is however contradicted by the available images.

The «self-defense» refuted by videos

Questioned by the IGPN and by the investigating judge, police officer Brice C. justified his action by invoking «self-defense»: he would have thrown his grenade in response to «a rain of projectiles» that was falling on his group.

This version of the facts is however refuted by the images that we have analysed and that we publish today.

On the one hand, that particular group of policemen did not seem to have been the target of any projectile during the seven seconds which elapsed between their stop in the middle of the square and the throwing of the de-encirclement grenade.

On the other hand, the grenade throw is carried out in the direction of a group of demonstrators who are in no way «hostile» and do not present any apparent danger to the police.

Among the twenty individuals present around Jérôme Rodrigues, the videos allow to identify several journalists or videographers busy filming the scene, as well as four volunteer paramedics – or ‘street medics’ – clearly identifiable by their white outfit. Yet it is this group that is targeted by a de-encirclement grenade.

The testimony of Brice C., author of the throwing of the grenade, is not the only one to be formally belied by the detailed analysis of the videos of the incident. Questioned as part of the investigation entrusted to the IGPN, at least eleven of his fellow colleagues support the version of Brice C., despite the images which invalidate it.

Contacted by INDEX before the publication of this investigation, the lawyer of Brice C., Gilles-William Goldnadel, maintains that «the group of [his] client was the object of violence and his gesture was part of an act of defense of his colleagues and himself in a climate of extreme tension.»

On January 14, 2021, police officer Brice C. was indicted for «wilful violence resulting in mutilation or permanent disability.» This criminal qualification is liable to a trial at the assizes. Nevertheless, the continuation of the judicial procedure until a possible conviction of the police officer is far from being guaranteed, in light of the recent history of this type of case.

In December 2022, the assizes held the trial of police officer Alexandre M., who had thrown a de-encirclement grenade which had blinded trade unionist Laurent Theron, in 2016, in circumstances comparable to those that led to the mutilation of Jérôme Rodrigues. Officer Alexandre M. was acquitted after three days of trial. The court found that he had acted in self-defense, even though an IGPN report found that «no hostile group or imminent danger was perceptible» at the time when the grenade was thrown. During his closing argument, the officer’s lawyer, Laurent-Franck Liénard, had bluntly alerted the court: «to condemn my client is to castrate all CRS», the acronym of the French anti-riot police.

De-encirclement grenades: a French exception

The incident that caused the mutilation of Jérôme Rodrigues is far from being an isolated case. Between September 2016 and April 2023, at least ten people were blinded by de-encirclement grenades thrown by the police. The website violencespolicières.fr has identified more than 400 other injuries, 17% of which to the head.

According to the available research, the French police is the only one in Europe that use de-encirclement grenades in crowd control contexts. Civil society organisations have been warning about this danger for years. According to Amnesty International, «de-encirclement grenades must be prohibited during crowd control operations because [their] projectiles randomly strike people with a high risk of serious injury».

The Défenseur des Droits, an independent administrative authority whose task is to defend citizens’ rights, also noted that the use of such grenades is «likely to seriously harm the physical integrity of those affected», in a decision rendered in 2019 on the case of a demonstrator injured in Paris in 2016. Jacques Toubon, who held the office at the time, had then invited the Minister of the Interior to «engage in an in-depth reflection on the relevance of the allocation, for law enforcement and crowd control operations, of this kind of weapon».

A few months later, in September 2020, the Minister of Interior Gérald Darmanin announced the replacement of the de-encirclement grenade (GMD) used by the police with a new model called ‘GENL’, presented as «less dangerous» than its predecessor.

However, the comparison of the technical sheets of the two models of grenades does not reveal any essential difference in terms of their dangerousness: the new GENL remains a grenade whose fragments are likely to seriously harm the physical integrity of people near its point of explosion.

Since the beginning of the social movement against the pension reform in January 2023, at least one new case of a demonstrator having lost an eye due to the explosion of a de-encirclement grenade has been recorded, as well as dozens of new injuries.

Credits

| Investigation / Analysis | Francesco Sebregondi Filippo Ortona Nadav Joffe Lorène Albin Basile Trouillet |

| Modeling / 3D Animation | Lorène Albin Nadav Joffe Thibault Casteigts Laïss El Khaledi |

| Editing / Motion Design / Voice | Basile Trouillet |

| Coordination / Realisation | Francesco Sebregondi |

Press

| Le Media 08.06.2023 | Comment la police a éborgné Rodrigues : une reconstitution exclusive détruit la version officielle |

| France Culture | Open Source 10.06.2023 | Éborgnement de Jérôme Rodrigues : reconstitution des faits |

| Au Poste 11.06.2023 | Éborgnement de Jérôme Rodrigues: le making of de l’enquête d’INDEX |